The Constitution elaborated neither the exact powers and prerogatives of the Supreme Court nor the organization of the Judicial Branch as a whole. Thus, it was left to Congress and to the Justices of

the Court through their decisions to develop the Federal Judiciary and a body of Federal law.

The establishment of a Federal Judiciary was a high priority for the new government, and the first bill introduced in the United States Senate became the Judiciary Act of 1789. The act divided the

country into 13 judicial districts, which were, in turn, organized into three circuits: the Eastern, Middle, and Southern. The Supreme Court, the country's highest judicial tribunal, was to sit in

the Nation's Capital, and was initially composed of a Chief Justice and five Associate Justices. For the first 101 years of the Supreme Court’s life -- but for a brief period in the early

1800s -- the Justices were also required to "ride circuit," and hold circuit court twice a year in each judicial district.

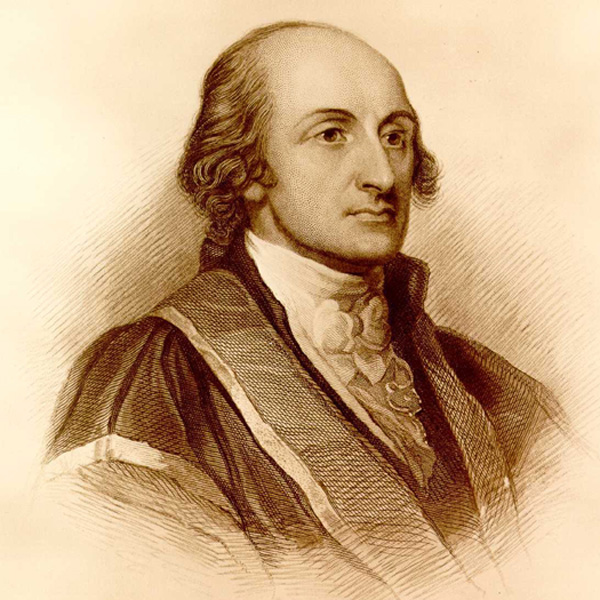

The Supreme Court first assembled on February 1, 1790, in the Exchange Building in New York City -- then the Nation’s Capital. Chief Justice John Jay was, however, forced to postpone the initial

meeting of the Court until the next day since, due to transportation problems, some of the Justices were not able to reach New York until February 2.

The earliest sessions of the Court were devoted to organizational proceedings. The first cases reached the Supreme Court during its second year, and the Justices handed down their first opinion on

August 3, 1791 in the case of West v. Barnes.

During its first decade of existence, the Supreme Court rendered some significant decisions and established lasting precedents. However, the first Justices complained of the Court’s limited stature; they were also concerned about the burdens of “riding circuit” under primitive travel conditions. Chief Justice John Jay resigned from the Court in 1795 to become Governor of New York and, despite the pleading of President John Adams, could not be persuaded to accept reappointment as Chief Justice when the post again became vacant in 1800.

Consequently, shortly before being succeeded in the White House by Thomas Jefferson, President Adams appointed John Marshall of Virginia to be the fourth Chief Justice. This appointment was to have a significant and lasting effect on the Court and the country. Chief Justice Marshall’s vigorous and able leadership in the formative years of the Court was central to the development of its prominent role in American government. Although his immediate predecessors had served only briefly, Marshall remained on the Court for 34 years and five months and several of his colleagues served for more than 20 years.

Members of the Supreme Court are appointed by the President subject to the approval of the Senate. To ensure an independent Judiciary and to protect judges from partisan pressures, the Constitution provides that judges serve during “good Behaviour,” which has generally meant life terms. To further assure their independence, the Constitution provides that judges’ salaries may not be diminished while they are in office.

The number of Justices on the Supreme Court changed six times before settling at the present total of nine in 1869. Since the formation of the Court in 1790, there have been only 17 Chief Justices* and 104 Associate Justices, with Justices serving for an average of 16 years. Despite this important institutional continuity, the Court has had periodic infusions of new Justices and new ideas throughout its existence; on average a new Justice joins the Court almost every two years. President Washington appointed the six original Justices and before the end of his second term had appointed four other Justices. During his long tenure, President Franklin D. Roosevelt came close to this record by appointing eight Justices and elevating Justice Harlan Fiske Stone to be Chief Justice.

*Since five Chief Justices had previously served as Associate Justices, there have been 116 Justices in all. This included former Justice John Rutledge, who was

appointed Chief Justice under an interim commission during a recess of Congress and served for only five months and 14 days in 1795. When the Senate failed to confirm him, his nomination was

withdrawn; however, since he held the office and performed the judicial duties of Chief Justice, he is properly regarded as an incumbent of that office.