Harlan Fiske Stone: A Man for All Seats

The Associate Justice Years (1925–1941)

“I have never found anything quite so absorbing as work on the Supreme Court. It just seems to exclude everything else.”

— Stone, writing to his sons, April 13, 1933

Confirmation

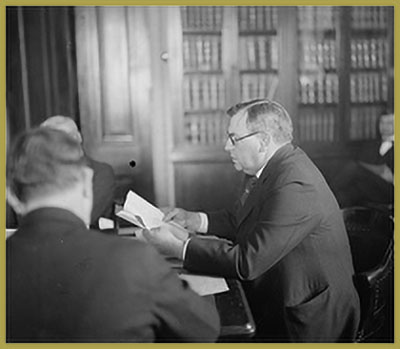

In January 1925, Associate Justice Joseph McKenna’s retirement created a vacancy on the Supreme Court, and President Coolidge again looked to Stone. The Senate Judiciary Committee recommended Stone’s confirmation to the full Senate. However, some Senators had additional questions and returned the nomination to the Committee for further review. Stone consented to appear in person before the Committee—a first in Supreme Court and Senate history. His strong performance, fielding questions during five hours of public testimony, cleared the path for his confirmation. On February 5, 1925, the Senate confirmed the nomination by a 71 to 6 vote, and Stone officially joined the Supreme Court on March 2, 1925. While Stone’s appearance was historic, it was not until 1955 that the Senate Judiciary Committee made in-person hearings a requirement for Supreme Court nominees.

Stone appearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee, January 28, 1925.

Stone appearing before the Senate Judiciary Committee, January 28, 1925.

Library of Congress

1 / 3

Retired Justice Joseph McKenna (right) and Attorney General Harlan Fiske Stone, January 1925.

National Photo Company

2 / 3

Stone poses for photographs after being sworn in as an Associate Justice by Chief Justice William Howard Taft, March 2, 1925.

International Newsreel

3 / 3

In Stone’s era, Justices used docket books to keep notes and records of actions taken on petitions for certiorari, cases, motions, and miscellaneous matters before the Court. This book dates from Stone’s first Term on the Court.

❮

❯

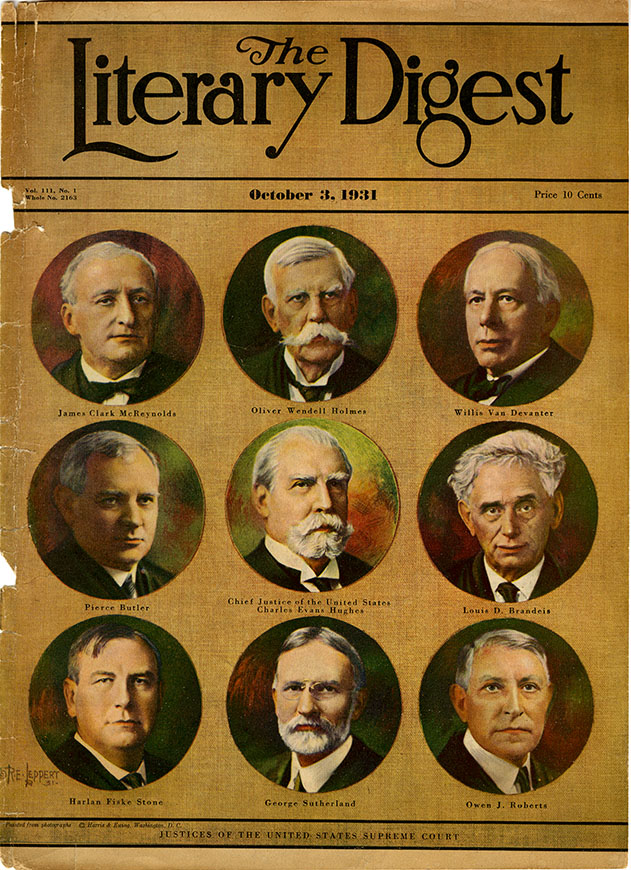

Stone (bottom row, left) and Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., (top row, center) and Louis D. Brandeis (middle row, right), were frequent companions in dissent.

Stone (bottom row, left) and Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., (top row, center) and Louis D. Brandeis (middle row, right), were frequent companions in dissent.

Harris & Ewing, R.E. Leppert

Joining the Dissenters

Stone’s appointment marked the end of a tumultuous period on the Court during which eleven appointments occurred in just fifteen years. The new Justice’s somewhat moderate stance on the legal issues of the day, including New Deal programs, often found him in disagreement with the Court’s majority. The phrase, “Brandeis, Holmes, and Stone, dissenting,” became commonplace in Court opinions, as Stone frequently joined Justices Louis D. Brandeis and Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., in dissent. By the late 1930s, however, continued changes to the Court’s makeup reversed this trend. When the Court began to uphold the constitutionality of New Deal legislation, Stone more often found himself in the majority.

“The library where I spend most of my working hours when I am not in Court is especially attractive. It is so quiet and the light is so good that I feel like a different man.”

— Stone, writing to his sons, February 9, 1928

The Stones Build a Home in Washington, D.C.

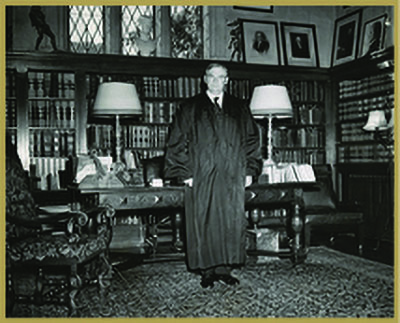

When Stone became a Justice in 1925, the Court held its sessions in the former Senate chamber of the U.S. Capitol Building. Lacking office space in the Capitol, the Justices typically worked from home. When the Stones planned their new house at 2340 Wyoming Avenue NW, they incorporated a large home office and library. Milton C. Handler, a law clerk in the 1926 Term, recalled that Stone visited the construction site daily, personally examining “every bit of material that went into the house.” Agnes Stone commented, “Between the architects and ourselves, little was put over on us.” The Stones moved into their home in 1927.

Stone standing in his home office, October 4, 1941.

Stone standing in his home office, October 4, 1941.

Harris & Ewing

Working from Home

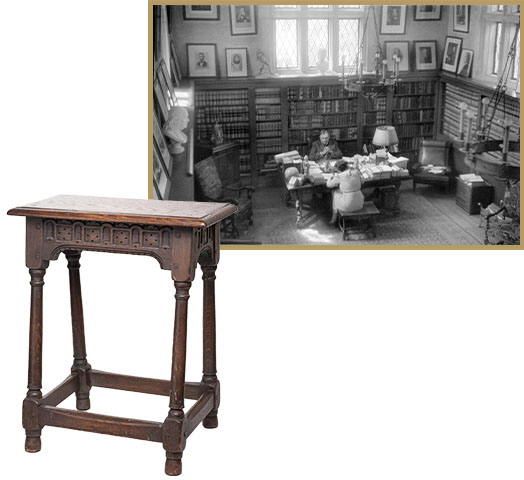

Stone spent considerable time working in his home office. Gertrude Jenkins, his longtime secretary, had an office on the same floor, while the Justice’s law clerks worked in a balcony above. Stone chose to decorate his office with Colonial Revival furniture, including a large desk now at Columbia University and a joint stool (right) featuring pegged mortise-and-tenon joints indicative of the style, c. 1927.

Stone and longtime secretary Gertrude Jenkins in his home office, c. 1937-1938.

Stone and longtime secretary Gertrude Jenkins in his home office, c. 1937-1938.

Louis Lusky

View from the east of the Supreme Court Building during construction, August 1, 1933.

View from the east of the Supreme Court Building during construction, August 1, 1933.

Commercial Photo Company

The New Supreme Court Building

Several years after moving into his new home, Stone consulted with Chief Justice William Howard Taft on another construction project, the Supreme Court Building. When the building opened in the summer of 1935, Stone’s reaction was less than favorable. “A day or two ago I visited the Supreme Court building into which I suppose we will move sometime next year,” he wrote to his sons on May 24, 1935. “It is a very grand affair, but I confess that I returned from my visit with a feeling akin to dismay. The place is almost bombastically pretentious, and thus it seems to me wholly inappropriate for a quiet group of old boys such as the Supreme Court of the United States.”