Forgotten Legacy:

Judicial Portraits by Cornelia Adèle Fassett

Electoral Commission of 1877

Capturing a Moment in History

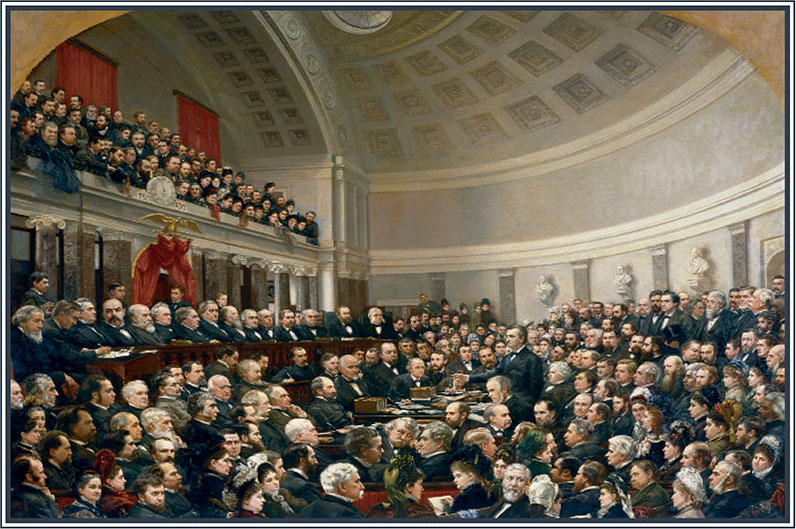

After the Electoral Commission of 1877 settled the disputed 1876 presidential election in favor of Rutherford B. Hayes, Fassett set out to capture the Commission’s momentous decision for posterity. In order to render the original setting of this historic event accurately, she was given permission to paint in the U.S. Capitol’s Supreme Court Chamber during the summer recess of 1877 and 1878. Completed in the grand manner of history painting, the composition depicts William M. Evarts, counsel for Hayes, addressing the Commission. In addition, Fassett included more than 250 individual portraits painted from life and photographs.

The Florida Case before the Electoral Commission by Cornelia Adèle Fassett, 1879.

The Florida Case before the Electoral Commission by Cornelia Adèle Fassett, 1879.

U.S. Senate Collection

History paintings often depict a narrative in classical, mythological, or biblical history. The genre was regarded in academic circles as one of the highest forms of painting because the artist had to portray complex subject matter in addition to demonstrating artistic skills. By the 19th century, some American artists, such as Fassett, adopted this genre to glorify and memorialize important events in the history of the United States.

The Commission

In January 1877, Congress created a 15-member Electoral Commission charged with resolving 20 disputed electoral votes from the states of Louisiana, South Carolina, Florida, and Oregon. The Commission was comprised of five Senators, five Representatives, and five Supreme Court Justices. Although Justice David Davis was originally selected for the Commission, he declined, and Justice Joseph P. Bradley filled his seat. The most senior Justice, Nathan Clifford, served as President of the Commission.

Fassett often worked from photographs taken by Samuel Montague Fassett, as well as by noted Civil War photographer Mathew Brady. The photographs above may have been used by Fassett while completing work on her depiction of the Electoral Commission.

Take A Closer Look

Move your cursor over the figures on the Bench to reveal the identity of each member of the Electoral Commission.

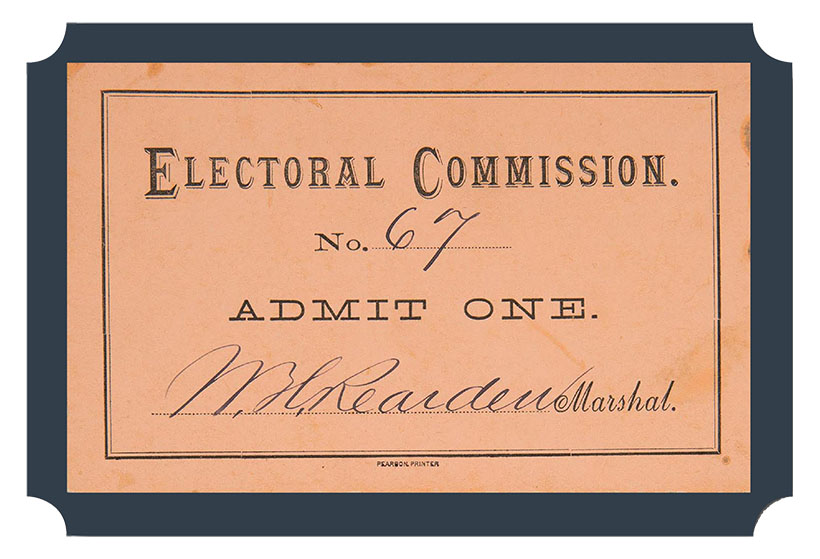

Admission ticket to a public hearing held by the Electoral Commission, signed by W.H. Rearden.

Admission ticket to a public hearing held by the Electoral Commission, signed by W.H. Rearden.

Making a Social Statement

In addition to documenting the Electoral Commission, Fassett sought to make a bold statement about the place of women in society. More than 60 women are included in the painting, including female journalists, artists, and authors, many of whom were not actual witnesses to this historic event. Fassett highlighted the importance of the women’s rights movement by including suffragists, such as Mary Clemmer Ames. From 1866 to 1884, Ames gained national attention for her New York Independent column entitled, “Woman’s Letter from Washington,” in which she often advocated for suffrage and equality.

Also included on the main floor are several African Americans. Well-known orator and abolitionist Frederick Douglass is featured prominently in the middle ground, while Supreme Court Messenger Annanias Herbert and Doorkeeper Gustavus Clark appear on the periphery of the painting. Fassett probably came to know Herbert and Clark while she was painting in the Chamber, and perhaps included them as a commentary on their position on the edge of society as the Reconstruction era was coming to an end.

Self-portrait of Cornelia Adèle Fassett, detail from The Florida Case before the Electoral Commission, 1879.

Self-portrait of Cornelia Adèle Fassett, detail from The Florida Case before the Electoral Commission, 1879.

U.S. Senate Collection

Fassett’s Self-Portrait

The only known self-portrait of the artist is also featured, and depicts Fassett at work, with a sketchpad in hand. Fassett portrays herself as an onlooker and recorder and, perhaps more importantly, represents herself as a professional artist.

Lasting Legacy

Despite her generally well-regarded reputation, Fassett’s most ambitious work was not initially well received. When the painting was offered to the Congress, objections to its purchase were raised by some, including a columnist for The American Architect and Building News, who claimed that Fassett did not have a “reputation which would justify the payment of such enormous prices out of the public treasury for [her] works.” After two failed attempts, the Senate finally acquired it in 1886 and displayed it in the U.S. Capitol Building, where it remains today. Fassett’s persistence in persuading the government to purchase her painting, as well as her decision to include a self-portrait, are a testament to her commitment to her art and her determination to help pave the way for future female artists.